Andrew Nixon

Stillness and Motion

Artist's Reception June 6th, 5-7PM

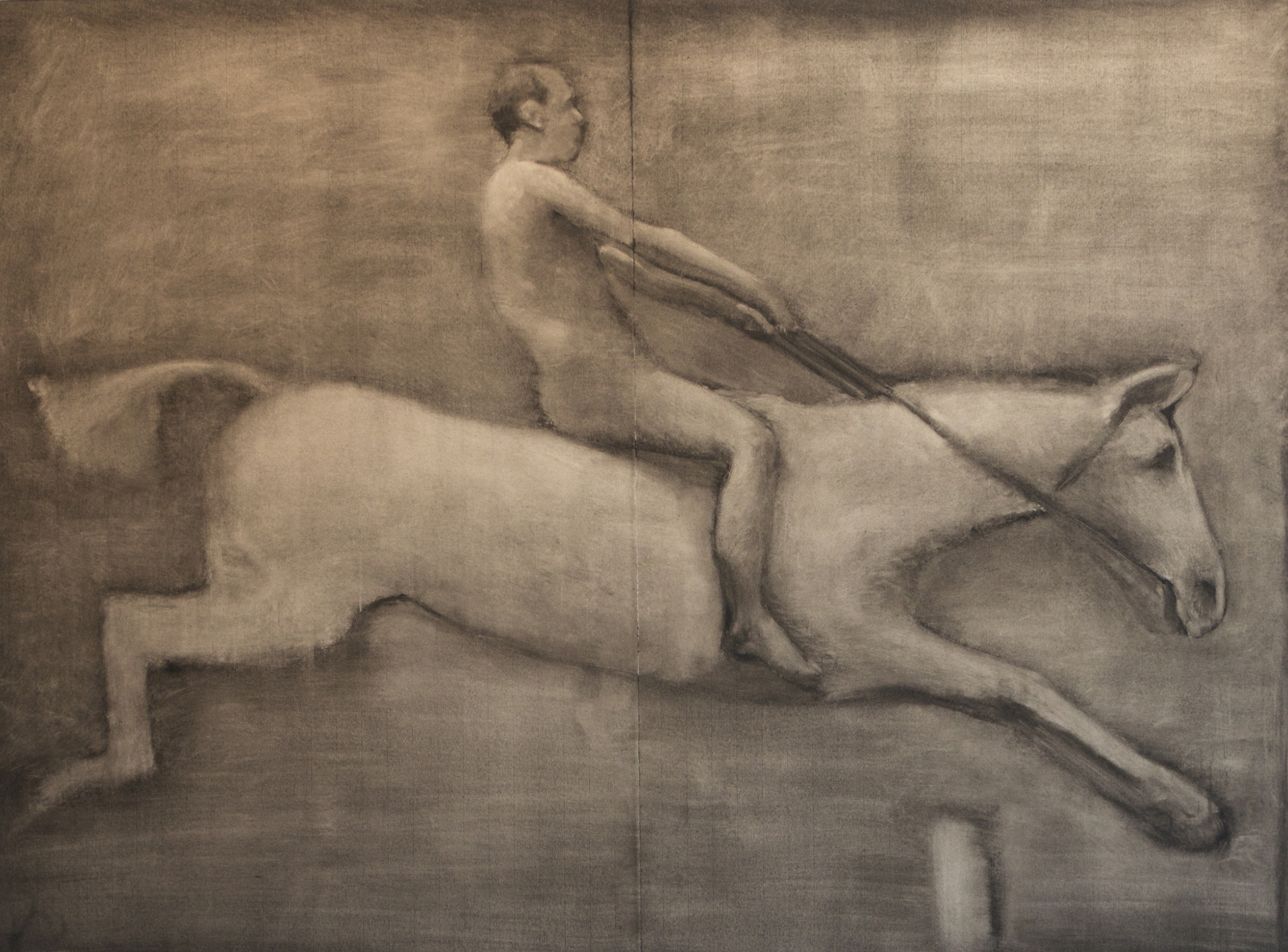

Dedee Shattuck Gallery is pleased to present Stillness and Motion, a solo exhibition of recent paintings by Andrew Nixon. This exhibition focuses on the relationship between photography and painting, where the two fields intersect and complement each other. Nixon’s ability to seamlessly combine the two genres is an elegant nod to the works of post impressionist Georges Seurat (1859-1891). This exhibition displays Andrew Nixon’s interpretation of works taken from Eadweard Muybridge’s stills (1830-1904), who famously photographed and analyzed the motion of humans and animals beginning in 1872.

The animals Nixon paints in Stillness and Motion, are moments within a lifetime of motion. Each painting is a reminder of the power and beauty belonging to the animal, while alluding to the significance of form, shadow, depth and light. Nixon’s painted works freeze animals in time, the inconsistency created by the single touch of the brush are specific and experimental choices.

Andrew Nixon is a native of Rhode Island and he now calls South Coast Massachusetts his home. He received a Bachelor of Fine Arts at Boston University from the School of Visual Arts and a Master of Fine Arts from the Hope School of Fine Arts at Indiana University. Currently Nixon teaches at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth in the Visual Arts Department.

Stillness and Motion, examines the genres of painting and photography, Nixon writes “A successful painting will reward patience by disclosing itself over time.” Dedee Shattuck Gallery is honored to host this solo exhibition.

Bio

Andrew Nixon’s paintings explore stillness, light, form, and space. His influences range from ancient Egyptian sculpture to the paintings of Danish Modernist Wilhelm Hammershøi. A native of Rhode Island, he holds a BFA degree from the School of Visual Arts at Boston University and an MFA from Indiana University’s Hope School of Fine Arts.

Nixon’s paintings have been widely exhibited in numerous one-person and group shows in the United States and Europe. His work is in the Rhode Island School of Design Museum, the Newport Art Museum, the Stewartry Museum in Scotland, and several corporate collections.

He is a winner of the 2012-13 Pollock Krasner Foundation Grant.

He teaches studio art courses at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth.

Memory Holloway and Andrew Nixon Interview

April 30, 2015

Missing Parts

For some time Andrew Nixon has looked at the small drawings by Seurat and Muybridge’s photography of animals. His paintings suspend cats in motion in mid- air as a way to study movement. This contradiction is one that he likes. It links him to stillness and to flux at the same time, his way of marking his difference from Muybridge. In his drawings he works with conte and oil stick in a flurry of dense velvety lines that recall the small studies that Seurat did in the late 19th century. He is more interested in the strange silhouette of an animal than making it look real. There are missing parts in the animals, cats with no eyes, elk with tiny feet, quirky mules that kick on command, a sturdy bison, shadows that don’t quite add up. We drink some tea from a thermos, and he reads from a review on a recent show of contemporary painters at MOMA and he talks about the “old, slow art of the eye and the hand in service to the imagination.” For a long time, he says, we’ve been told that painting is in crisis, but here it is, unlike anything else, where seeing and touch show us the singular troubles and glories of picture making. In a time of quickly spinning data and overwhelming information, painting demands that we take the time to look. Time suspended, details cut from our expectations. This is the force of Andrew Nixon’s work.

I met him in April In his studio, where we talked about art and science, missing parts, the French in Woonsocket and the future of painting.

MH You were born in Cumberland, Rhode Island.

AN Well, born in Woonsocket, Rhode Island, to be precise, but I lived in Cumberland all my young life.

AN My mother was from Woonsocket and my father was from Lincoln, RI.

MH Did they encourage you in art making?

AN Yes and no. They could see that I was good at it. My dad especially worried that I would not be able to make a living at it. When I graduated I got an interview at Hasbro at his insistence. This was in the ‘80s. I did well in the interview and they offered me a lot of money. I just thought, I can’t do this. My parents had just paid for a really great education, and I couldn’t spend it making G.I. Joes. My dad was disappointed.

MH Where did your interest in the arts come from?

AN My dad said he wanted to go to RISD but ended up going to World War II instead, and by the time he got out, everything had changed. He was bitter about that. My mother’s father was an upholsterer, he had his own shop and made furniture and drapes by hand. Before I went to elementary school, I spent a lot of time with my grandfather in the shop. He was one of the happiest people I have ever known, just making the things he wanted to make. He was a singer and calligrapher and was very good with his hands. My maternal grandmother was a pianist and church organist who also taught music. She was born in Canada and my grandfather was born in Rhode Island but they were both completely French-Canadian. You know, until the late 1960s, French was the predominant language in Woonsocket.

MH Did you hear it growing up?

AN Oh yeah, all my aunts spoke French. When you went to Woonsocket you didn’t really know what was going on.

MH What about food?

AN I love food!

MH (laughs) Do you eat poutine? Were any of those French-Canadian dishes in your childhood?

AN Well, …there were many bechamel cream sauces that my grandmother made. Her father was a doctor and although she worked for a living and cooked well, she thought it was beneath her.

MH You have been looking a lot at Muybridge (b.1830-1904).

AN He called himself Helios for a while, and his studio was called Helios studio. I think there is no definitive way to pronounce his name.

MH How would you describe the process of looking at Muybridge, adapting and extracting, how does he feature in the work?

AN He made over 100,000 photographs. I look at the series and I look for images, images that I feel are vague enough, and have the potential to be made my own.

MH What does that mean “making it your own?”

AN To not be derivative, I have to transform the image. I have to begin with his original work and then figure out how to make it new.

MH How do you transform it?

AN By selectively amplifying some things and excluding others. For example (referring to the painting 16 Cats) these cats have no eyes, and I am making an attempt to translate the movement, and not the specifics of the form. I’m trying to do it in a similar way to what Seurat did. Cognitive psychologists say that the way we process images is to break down the visual information into two groups; one is what it is, the other is where it is, and then the information is combined again to form the image we perceive. Seurat’s drawings are only where it is, not what it is. You can only understand his form by its context. In his images if you look at something specific like an animal’s head, you can only understand it by looking at the whole image.

MH Are you saying Seurat does not provide a context for us?

AN Oh he does, but it is the context of the rectangle, where things are in relation to other things in the whole frame. It’s a really controlled narrative, so much is left out.

MH But he does in the Sunday afternoon on the Isle of the Grand Jatte. That is a really contextualized image. Those drawings, after drawings, after drawings, have a landscape context.

AN Yes and that is a painting that doesn’t interest me(laughs)! I understand what a heroic effort it was, but the studies are what really excite me. He saw himself almost as a scientist who approached his work in an objective manner. He also said almost anyone could do it, which of course, wasn’t true.

MH Do you see yourself this way? What is the distinction you make between science and art? Do you see this (referring to the paintings) as in any way, a scientific endeavor?

AN No, because I am not using scientific method, and Muybridge was kind of a fake scientist. He sold himself as one, but he wasn’t rigorous.

I want to read you something. It’s from the book Geek Sublime by Vikram Chandra. In the book he describes a problem in computer software coding that was solved by what is called “event sourcing.” This guy is a novelist but he has also had a career as a coder. The problem he describes, if you had something like a database and you had several users, every time someone added to the database it would change the structure of the code, the original structure would get lost and too complicated. So they solved this problem through event sourcing, meaning whenever a keystroke was made, it was recorded as a specific event, much like a photograph. Through event sourcing, the individual using the software has an experience of a whole form but actually it is a cumulative record of specific events. I’m making a long point here but in it he says:

“As I learned the beauty of the event sourcing, I was reminded of other discussions of identity over time that had been on my mind. The Buddhists of the Yogacharya school (4th century CE) were among the proponents of the doctrine of no-self, arguing what appears ‘to be a continuous motion or action of a single body or agent, is nothing but a successive emergence of distinct entities in distinct yet contiguous places’.”

MH Distinct entities.

AN “Distinct entities in distinct yet contiguous places.” So it’s amazing to me that these Buddhists in the fourth century were thinking about life as being not continuous but life being a series of events that are next to each other. And I thought, that’s Muybridge.

MH Is that you also?

AN I think it’s a really open question. There’s a philosopher name Derek Parfit at Oxford who has written about seeing his own identity in this way. He believes that there is no self, there is just a series of experiences. I don’t know. I do think that the relationship between the individual frame and motion presents that same philosophical question.

MH This frame and motion, what is that? Is the frame a fixed event, how do you see that metaphorically?

MH There’s a variety here, of what you might call naturalism and geometry. Do you see it that way? Are they naturalistic in any way, or realistic if we want to call it that?

To continue reading this interview click here.

Dedeeshattuckgallery.com | 508. 636. 4177 | 1 Partners' Lane, Westport, MA 02790 | W - Sat, 10 - 5, Sun 12 - 5